Please forward this to ONE friend today and tell them to subscribe here.

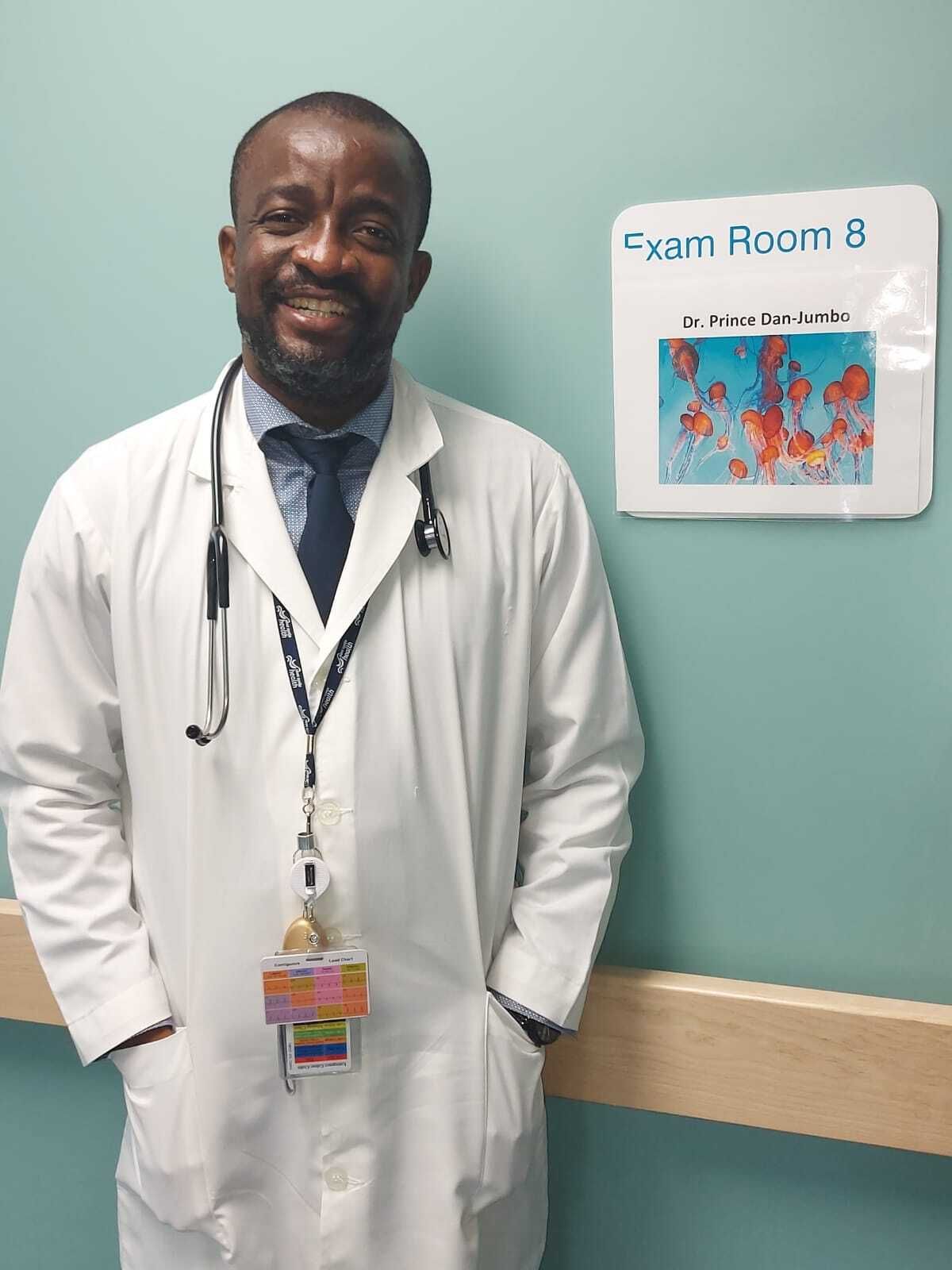

Dr. Prince Dan-Jumbo during his time as a Family Physician at UniPort Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

In the last five years, Nigeria lost about 15,000 to 16,000 doctors to the Japa syndrome, while about 17,000 had been transferred.

Who’s surprised? Not me.

I graduated from Medical School in 2006 in Nigeria and worked as a family physician at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital for 12 years. Some days, I struggled to access the necessary resources to confirm a diagnosis.

On other days, I’d be protesting for my unpaid salaries. Sometimes, we’d be owed for six months.

Between the inefficiency of entering medical records manually, using outdated journals for seminars, and being harassed by the government for my rights, I had to find a way out.

Immigrating felt like gambling away my Nigerian work experience, with no guaranteed pay-off.

During the pandemic, I scoured the internet for information on the Canadian immigration process for medical personnel.

There are various pathways for immigrating to Canada as a medical doctor. Having trained as a family physician, I decided to apply through the Practice-Ready Assessment (PRA) immigration pathway.

PRA is an accelerated pathway for licensure in the Canadian healthcare system. It is less competitive than applying for medical residency because Canada has fewer than 25 medical schools, each with a large number of candidates for limited seats.

Landing in Canada

I moved to Canada with my family in November 2021 as a permanent resident (PR) and started studying for the Medical Council of Canada Q1 exam.

Preparing for the Q1 Exam

People often ask about exam materials. The Alberta International Graduate Medical Association supported us with resources like the USMLE Step 1, which is similar to the Canadian exam. We also used the Toronto Notes, a comprehensive guide for the Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Exams.

It's a voluminous book, so focus on these key areas: family medicine, Canadian Medical Protective Association guidelines and ethics, emergency medicine, pediatric genetics, obstetrics and gynecology prenatal care, cardiology (especially heart failure), and respiratory conditions like asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD).

Studying these areas will make the Q1 exam easier.

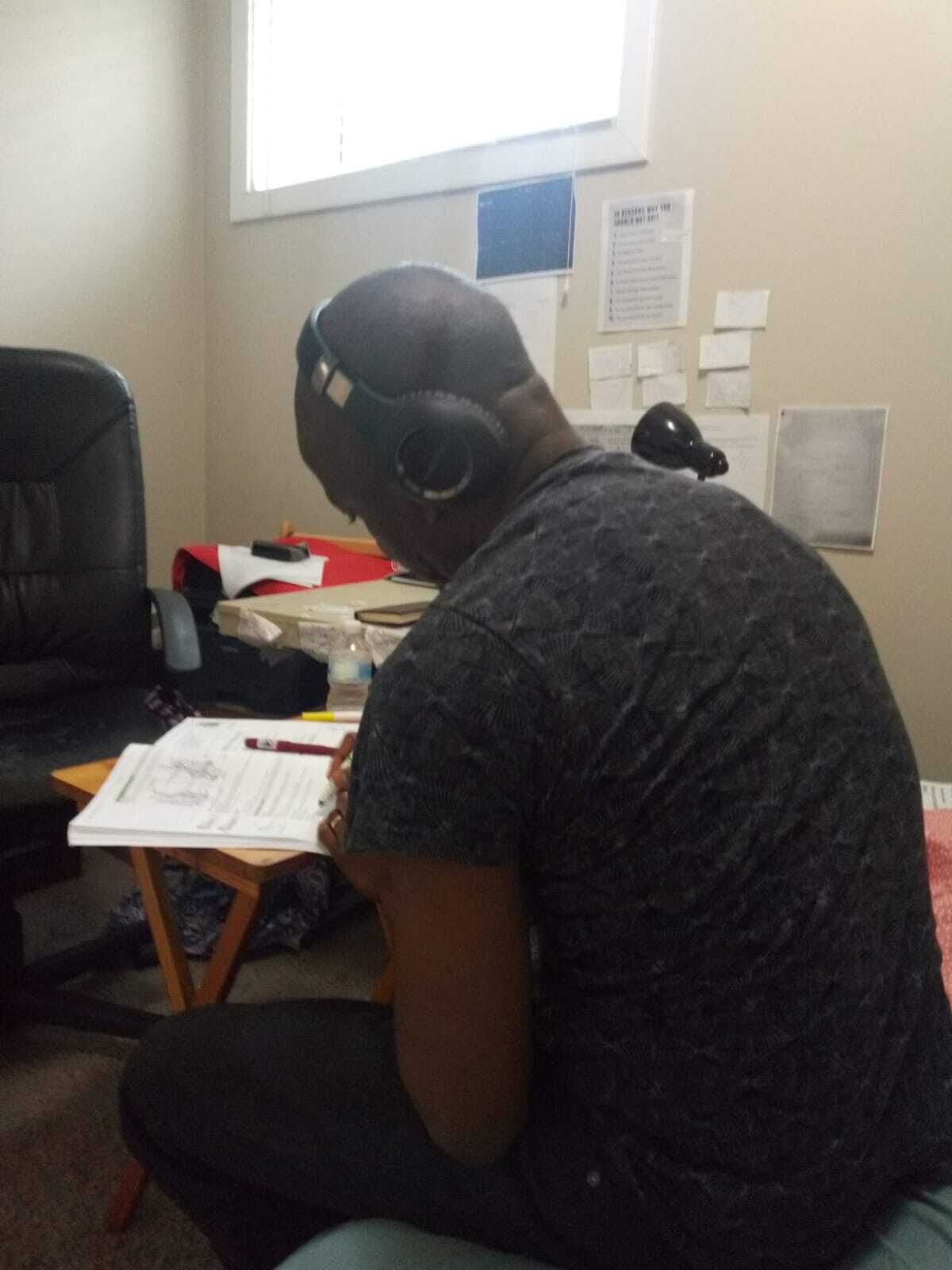

Studying for the Canadian Q1 exams.

Keep in mind that 60% of the final score is based on ethics, which are practiced differently here compared to back home.

The PRA process is straightforward. If you don’t have a PR, study for the exam while still in Nigeria, pass your Q1, and take the English test – either IELTS Academic (score 7 in all areas) or OET Medicine (B in all areas, equivalent to 350). Once you pass, you can apply to a province.

Choosing a Province

Each province regulates medical practice differently. I often advise folks to apply to Alberta or British Columbia because they offer LMIA.

The advantage for federal skilled workers is that you don't have to enter the pool or provide proof of funds. Once you pass the exam, the health authorities will apply for the work permit, allowing you to relocate, complete your assessment, and bring your family without needing proof of funds.

In Nova Scotia, you must first arrive and have a work permit or permanent residency to be eligible.

It took nearly a year to prepare and complete my Q1 exam.

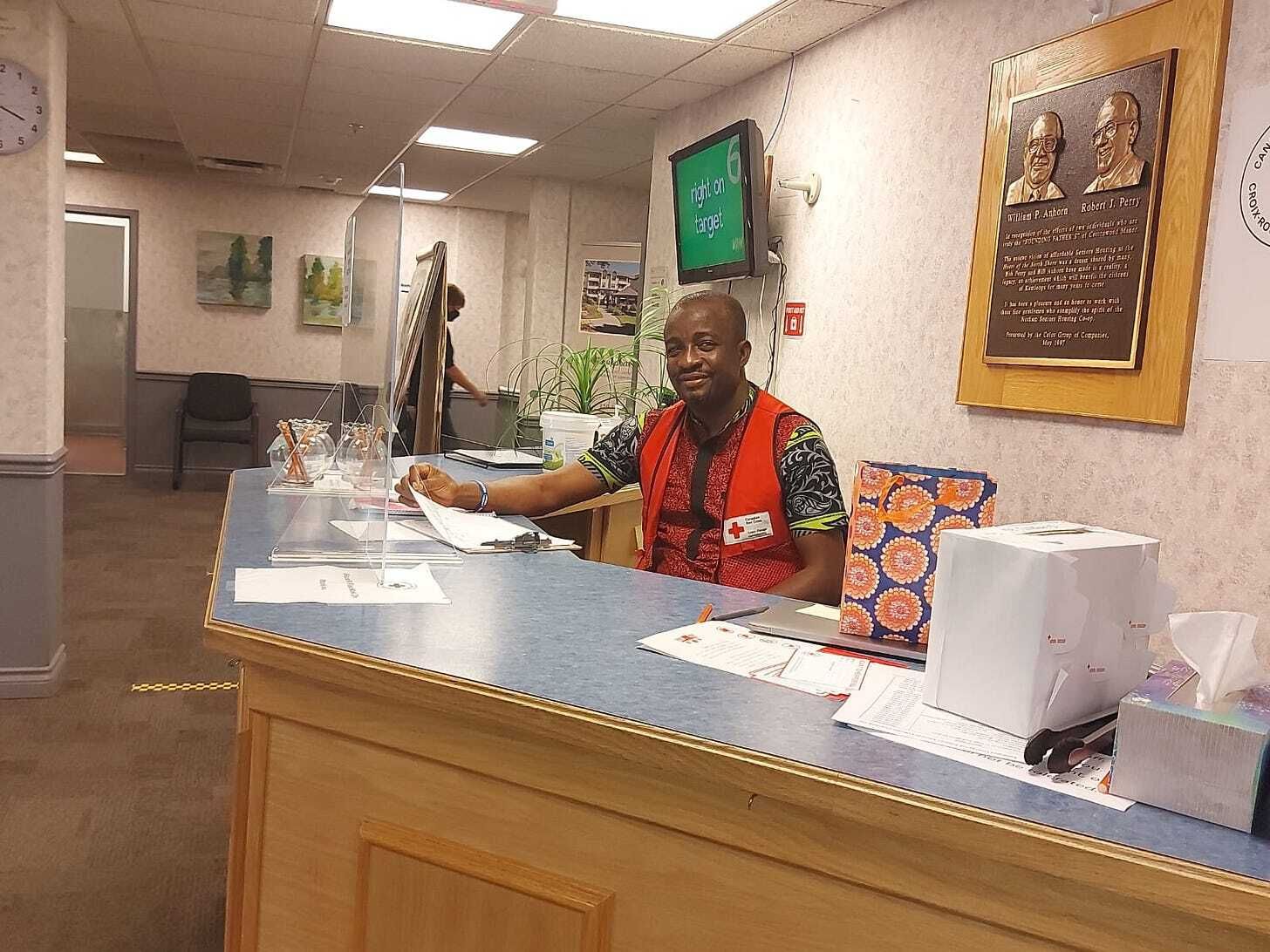

But man must wack. I took a job with the Canadian Red Cross as an Emergency Response Team Supervisor working with fire and flood victims.

Working at the Canadian Red Cross.

After passing my exams, I could start additional training like advanced cardiac life support and advanced trauma life support. I also enrolled in preparatory courses for provincial eligibility exams. After passing Q1, you need to apply to a province for ‘eligibility.’

The eligibility exam tests if you are a safe doctor, including how you prescribe medications.

After receiving my results, I applied to Nova Scotia, Alberta, British Columbia, and Newfoundland for eligibility to practice. Nova Scotia asked me to start in September 2022 and begin my three-month assessment.

I had to rotate with four consultants in two clinics, seeing at least 70 patients at each location to complete this stage. The assessment evaluated my knowledge based on patient interactions.

I finished the process in January 2023, began the licensing process with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Nova Scotia, and was approved to start practicing on March 3rd, 2023.

My First Six Months as a Licensed Canadian Doctor

I spent my first six months with a supervising mentor who helped me understand the patient referral system, access regional hospitals, find accommodation, and digitize medical records.

Woohoo! Approved to practice as a Canadian medical doctor.

It felt gratifying to be in a place where the system worked.

There are no obstacles to my growth or expertise. The system values my knowledge and experience and rewards my hard work.

Despite the high cost of African food and unpredictable weather, the insecurity level is low compared to back home. I get paid every two weeks, so I don’t need to chase down an accounts department person.

The system works.

I’ve had to adjust to the new realities of practicing medicine here.

Back home, we majored in tropical medicine, focusing on malaria, with occasional diabetes and chronic illness cases. Here, there’s a high prevalence of non-communicable diseases like hypertension, diabetes, thyroid disorders, cancer, and mental health challenges.

I had to let go of my old ways of practicing medicine and learn new ones.

In Nigeria, we take history in a straightforward manner focused on medical facts. In Canada, history taking is narrative-driven with the patient describing events before symptoms started, how they felt when they began, and any related circumstances.

So, if you’re planning to come over, practice your listening skills.

Ethics and courteous workplace communication are essential. Looking back, the delay was necessary for me to learn ethics, which makes up 60% of the Canadian exam.

Some people are impatient and don’t understand why the process is lengthy. But once you take the exam and begin practicing, you’ll realize it was preparing you for North America’s demands.

The process equips you with workplace communication skills. In Nigeria, I could directly approach a registrar and demand to see a patient. But here, no one does that. You have to be courteous and polite, even when requesting a patient review.

You must treat everyone with respect and uphold people’s rights. If a 16-year-old enters your clinic, respect their wish for discretion and confidentiality. You cannot contact their guardian against their wish. Here, children can exercise their rights.

The Journey to Becoming a Certified Doctor in Canada was Challenging

But it’s been rewarding.

Not everyone can say the same. Some come in, stay for three to seven years without success, and end up frustrated or depressed.

Despite the uncertainty of success as a doctor in the West, the mass exodus of young Nigerian doctors isn't slowing down.

The good thing is anyone considering emigrating as a medical professional now has access to a large network of people who can guide them, unlike us who left during COVID-19.

Back then, no one told us we could take the qualifying exams before relocating. We just packed and headed down here.

As I speak to you, people in Nigeria write the exams from home. After the exams, they apply to a province, mainly British Columbia or Alberta, receive a work permit, and travel to start the assessment.

They can start practicing in three to six months.

The process is now straightforward, and I wish I had all that information at the beginning. Reflecting back, I’m happy I left when I did. It was one of my best decisions in the last decade.

If you’d like to support this work, consider buying me a coffee.

*Man must wack: Pidgin English for a human must do what needs to be done to survive.